R.I.P. privacy? French police will be able to access suspects’ phone cameras and mics

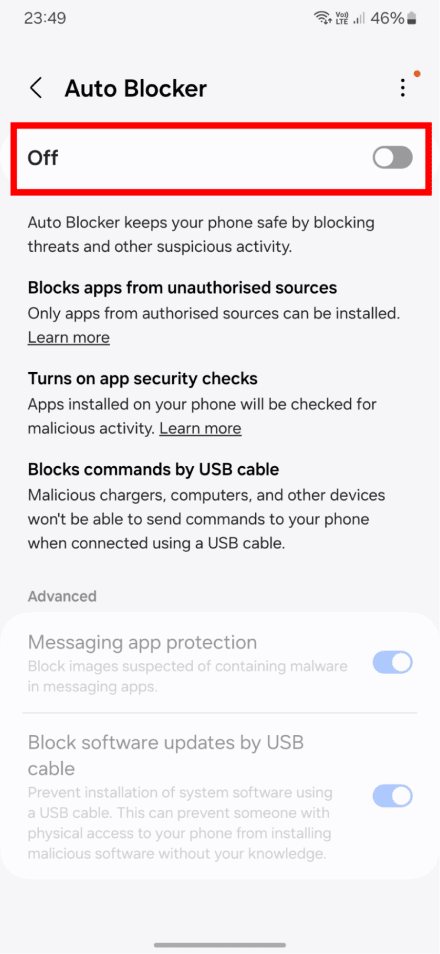

Members of the French National Assembly have overwhelmingly voted to approve part of a justice reform bill that could give police unprecedented powers to remotely monitor suspected criminals. The controversial Article 3 of the bill, which passed by a vote of 80-24, will allow police to remotely activate cameras, microphones, and geolocation systems in suspected criminals’ internet-connected devices — whether it be a car, laptop or mobile phone — without their knowledge or consent.

Law enforcement officials won’t be able to do this on a whim, but will have to get permission from a judge first. At the request of a prosecutor, the judge can authorize the remote activation of the device. However, the surveillance cannot go on forever under the same pretext: the judge can only authorize the monitoring for a total of up to 6 months, unless prosecutors come up with a new legal basis for it.

According to Radio France, the law covers serious crimes punishable by at least 5 years in prison. Contrary to what some might assume, it is not strictly limited to terrorism, but also applies to “delinquency and organized crime.”

It is worth noting that the article was originally intended to apply only to crimes punishable by at least 10 years in prison, but the bar was later lowered to 5 years. A representative of MoDem, a party allied to French President Emmanuel Macron, explained that the high threshold would have been too restrictive as it would have excluded certain crimes such as pimping and child abduction by a parent.

The worst is yet to come?

The article’s passing has sparked fears that the law could be used by the authorities to crack down on activists, and that France will slide further down the slippery slope of the surveillance state. The French environmental publication Reporterre pointed out that protests have sometimes been referred to by the authorities as criminal conspiracies. This would theoretically allow law enforcement to weaponize the bill to persecute protesters.

In addition, privacy advocates, up in arms over the bill, are concerned that over time the scope of the law could be expanded to include other crimes or that safeguards could be reduced. “Experience shows us that once a measure is approved, successive laws come to widen its scope,” a lawyer for digital rights group La Quadrature du Net told Reporterre.

As far as safeguards are concerned, the amended article explicitly states that the new police powers cannot be used to geolocate journalists, doctors, notaries, and bailiffs. The provision allowing for the remote capture of images and sound should not apply to members of parliaments, senators, judges, and lawyers in addition to all the above.

However, this has not appeased privacy groups, and rightly so. After all, it is not a good sign when the minister of justice has to refer to ‘1984,’ a famous novel by George Orwell that portrays a dystopian society under total surveillance, to defend the bill. During a parliamentary debate, French Justice Minister Eric Dupond-Moretti claimed that the bill would only affect “dozens of cases per year”, and insisted that it was neccessary to save people’s lives. “We are far from the totalitarianism of 1984,” he said.

France’s worrying descend into dystopia

Well, the country of égalité, fraternité and liberté may not have become a totalitarian nightmare yet, but the speed at which it is hurtling towards more surveillance and less ‘liberté’ is raising hackles.

In May, France’s constitutional court gave the green light to the use of AI-powered surveillance at the 2024 Paris Olympics. The measure, which would apply to sporting, recreational, and cultural events, will be in place until March 2025. Its approval made France the first country in the EU, an otherwise pro-privacy bloc, to allow the use of AI-powered surveillance, to the chagrin of privacy rights activists. That came after the French government allowed police, military and customs to use camera-equipped drones to monitor people in public places for the sake of thwarting terrorist attacks, but also to maintain public transportation, carry out border surveillance and rescue missions.

What about terrorism prevention?

The ultimate aim of these policies is to prevent terrorist attacks and other threats that could endanger hundreds of people. We can’t deny that this is a valid public interest, but it should not come at the expense of violating people’s privacy and rights.

Therefore, we need to ask ourselves: are these measures proportionate, and is there enough supervision to prevent power abuse? These questions are tricky, but it seems that spying on people who have nothing to do with terrorism, such as “delinquents,” is excessive. Moreover, adding yet another bill to pack of the surveillance-heavy laws can create more opportunities for abuse by those in power, which is a major concern.

Admittedly, there is no foolproof way to stop terrorist attacks, but constructing a surveillance society grounded in fear is definitely not the solution.