Smartphones collect vast amounts of personal data without consent. What can you do?

When you turn on your new smartphone for the first time, it is already jam-packed with apps that come bundled with it. Some of these pre-installed apps that clutter the screen and eat up your precious storage space at least may be useful. However, most of them you don’t need at all, but you play the hand you’ve been dealt.

On some smartphones, these apps can be uninstalled, although you may have to bend over backwards to do this. On others, they can only be disabled so that they do not run in the background. Besides, uninstalling system apps such as the built-in clock, phone or dialer apps can be risky, as it can turn your new phone into a brick.

It can be argued that having a manufacturer decide which apps you should have is no fun, but it is not a disaster either, and even convenient to some extent. After all, how bad can a messaging app be? But the problem is that built-in apps not only come to your phone uninvited, they also collect and transmit sensitive personal information back to the vendor or whoever the vendor deems fit. And because they’re system apps, they’re more likely to do so without your permission than apps that you download yourself.

Leaky phones

Researchers from University of Edinburgh and Trinity College Dublin have found that preinstalled apps on China’s three most popular Android phones are leaking users’ privacy-sensitive data, such as GPS coordinates, phone number, app usage, call history — all that without consent or, as in some cases, even without as little as notice.

In a paper called “Android OS Privacy Under the Loupe — A Tale from the East,” the researchers studied three popular Chinese smartphones: Xiaomi Redmi Note 11, OPPO Realme Q3 Pro, and a OnePlus 9R. In their interactions with the phones, the researchers acted as if they were “a privacy-aware but busy user,” who had opted out of analytics and personalization, did not use any cloud storage or any other optional third-party services, and had not created an account on any platform managed by the OS developer.

Not every user will go to such great pains to protect their privacy, but, turns out, even these precautions might fail. The researchers said that the smartphones were still sending “a worrying amount of personally identifiable information (PII)” not only to the device manufacturer, but also to mobile providers, including China Mobile and China Unicom. The twist is that the data was sent to these mobile network operators even if there was no SIM card in the phone, or if there was a SIM card from a different MNO, such as one based in the UK. Moreover, in some cases the data was also channeled to China’s search giant Baidu.

The same smartphones, but designed to be shipped outside of China, were found to be collecting significantly less personal data by default.

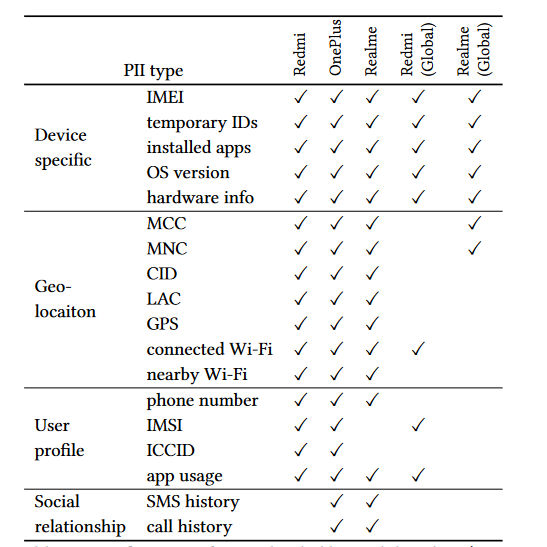

Table shows types of personal data (PII) uploaded by tested smartphones with Chinese and global firmware. Source: “Android OS Privacy Under the Loupe — A Tale from the East,” Liu et al.

A choice without choice

The researchers only looked at the data transmitted by pre-installed applications, and not the ones you install yourself. The former consisted of Android source code, vendor code, and third-party code. On average, the tested smartphones had “more than 30 third-party packages” pre-installed. An app can use multiple packages to run.

The pre-installed apps included navigation, news, streaming, shopping, and input apps. Some of the apps were granted dangerous permissions by default, transmitting sensitive information with no way for the user to opt out. In some cases, when users were notified that using the app required access to certain data, such as location, they were given a rather dubious choice: either not use the feature at all or agree to the data collection and sharing — an approach the researchers described as “take-it-or-leave-it”.

![]()

Diagram shows types of personally identifiable information (PII) collected by smartphones with Chinese firmware and locations it is being sent.

Whenever users agreed to give a system app carte blanche access to their personal data, they may have inadvertently revealed more about themselves than they bargained for. For example, the researchers found that phone and messaging apps bundled with OnePlus and Realmi not only sent the user’s phone number to the manufacturer’s servers, but also the duration of the call, ring time, last contact time and the number of a person the user was talking or texting with. Alibaba’s navigation app AMap on Realme and Oneplus was found to “regularly transmit GPS coordinates when the devices were idle.”

This treasure trove of information is directly linked to the user’s identity, and can reveal a lot about your personal life. The researchers note that, for example, broad access to call data can allow vendors to “infer the social relationships between users who are not directly connected.” In other words, the provider can deduce that your partner is likely to be cheating on you, while you may not even have a clue.

Long trail

Unsurprisingly, the smartphones with Chinese firmware do not stop spying on their owners once they leave the country, despite this potentially being in breach of local privacy laws, particularly EU data protection legislation. The researchers warn that this means that “phone vendors and some third parties are still able to track business travelers and students studying abroad, including the foreign contacts they make on their visits.” The same applies, of course, to non-Chinese citizens who happen to buy a smartphone manufactured for local distribution.

No, it’s not only about China

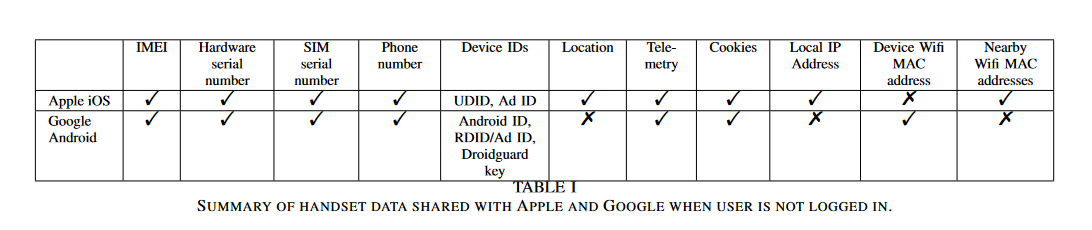

However, this does not mean that if you have not bought a phone in China or with Chinese firmware, there is nothing to worry about. While the scope of data collection by Android phones popular in China is alarming, the practice is not endemic to the country. Nor is it specific to the Android OS alone or the chosen brands. Previous research has shown that phones with both iOS and Android OS collect and transmit data to vendors, even when a user has opted out of data collection or hasn’t logged in.

In 2021 the co-author of this research, Douglas J. Leith also studied the amount of data shared by Google’s Pixel phone and Apple’s iPhone with Google and Apple, respectively. He found that both phones connect to the companies’ backend servers every 4.5 minutes on average, even when “minimally configured.” In the first 10 minutes of startup the Google phone sent to its mother ship 1MB of data, while the iPhone sent 42 KB of data to Cupertino. While both iOS and Android were found to share personal user data with manufacturers, Android did so on a much larger scale. According to the research, Google collected around 20 times more data than Apple.

Pre-installed apps on both the iPhone and Google Pixel also connected to the companies’ servers, even though they were never opened or used. On the iPhone, these included the Siri voice assistant, the Safari browser and iCloud, while on Google they included the YouTube app, Chrome, Google Docs, Safetyhub, Google Messaging, the Clock, and the Google search bar.

A big iOS privacy myth

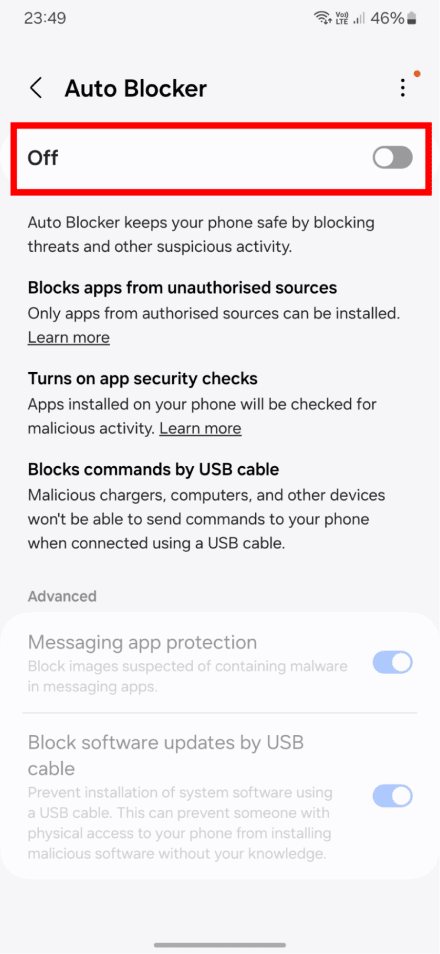

Apple has always positioned itself as a privacy champion, and while the research mentioned above can reinforce that impression, the issue is far more nuanced. If you have an Android-based phone, you can (at least in theory) disable Google services and apps, such as the Google Play store and YouTube, and prevent your data from being shared. That is because on Android you can sideload apps — in other words, you can install apps from sources other than the Google Play store.

With Apple, there’s no realistic way to use an iPhone without also using Apple’s App Store and other native Apple apps. There are rumors that Apple may allow sideloading in its next OS version in the EU, but so far these are just rumors. This means that iPhone users currently have no way to opt out of this kind of data sharing.

And, as researchers at the software company Mysk found last year, Apple is not passing up an opportunity to take advantage of the status quo. Mysk found that even when users turned off all personalisation options, including iPhone Analytics, Apple continued to collect detailed, real-time usage data from the iPhone’s native apps. The information the apps sent to Apple included a permanent ID number tied to the user’s name, email and phone number. This appears to be at odds with Apple’s own privacy policy, which claims that none of the information collected identifies the user personally.

What to do to minimize data collection

What makes this kind of OS-driven tracking so tricky is that you might not even know it’s happening. What’s more, often manufacturers will force or nudge you into agreeing to it without offering a viable alternative. It is borderline impossible to avoid it completely, but there are ways to minimize your online footprint.

System-wide ad blockers, armed with filters that include a long list of domains, can block ads and tracking across browsers and in third-party apps. Unfortunately, even system-wide ad blockers can’t stop all tracking, especially when it comes to device manufacturers themselves (such as Apple and Google) collecting information from their native apps. However, using an ad blocker will protect you from most third-party trackers, making your browsing experience safer and cleaner on the whole.

There are a number of system-wide ad blockers for different operating systems. One of them is AdGuard, which is available for both Android and iOS.