VPNs under attack in France: Everything you need to know

We have already given our take on the proposed French law, which is slowly making its way through the French parliament and which threatens to deal a fatal blow to the open Internet (or what’s left of it) and net neutrality. The law, called SREN, claims to fight online harassment and protect children from harmful content, but it also gives the government unchecked power to order web browsers and DNS resolvers to block any web page it deems illegal. This means that under the proposed law the government would be able to censor any website it dislikes without any judicial oversight or public accountability. In our previous article, we have explained why this is a dangerous and misguided idea.

But when it rains, it pours. Several newly proposed amendments to the law now also target VPNs (or Virtual Private Networks), which are tools that you can use to browse the Web securely and anonymously.

One of these amendments was introduced by Mounir Belhamiti of French President Emmanuel Macron’s Renaissance party, and the other by another ally of the French president, Horizons block member Vincent Thiébaut. Upon publication, these amendments have garnered a lot of traction and criticism from the opposition, digital rights advocates, journalists, and lawyers.

So, let’s take a closer look at them.

Making virtual anonymity a thing of the past

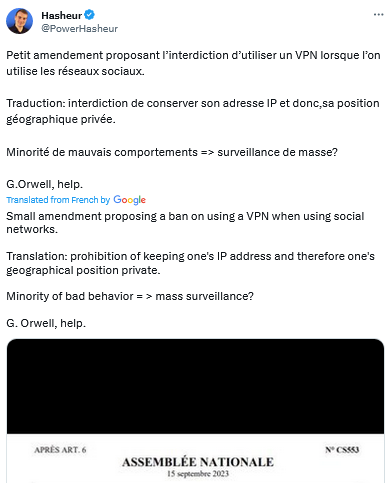

Belhamiti’s amendment is the most extreme of the two, proposing an outright ban on the use of VPNs on social networking sites. In justifying such a ban, the lawmaker argues that the rules of the physical world should also apply to the virtual world. To make his point, he compares social networks to “public roads” where there’s no place for anonymity, because if there were, traffic violations wouldn’t be punished. Belhamiti argues that online service providers should be able to punish criminals just like traffic cops, and to do that they need to know your IP address. The problem with VPNs, he says, is that they make it harder to identify online criminals… so, therefore they must be banned.

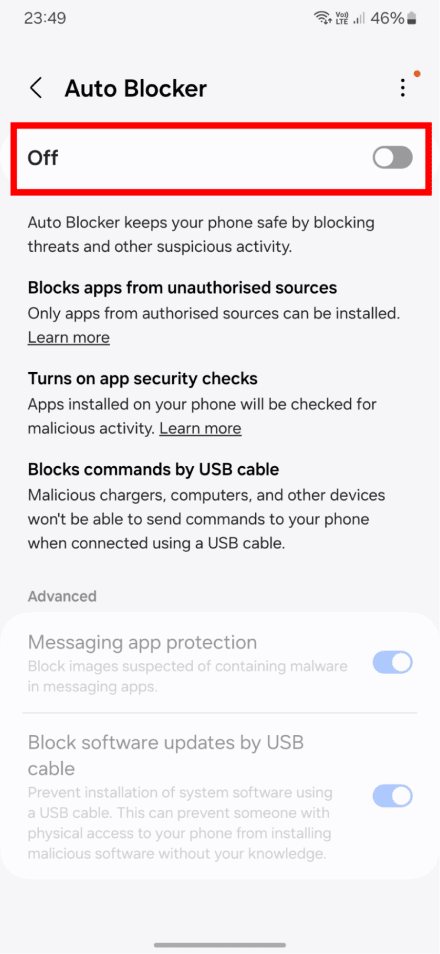

To ensure enforcement of the ban, Belhamiti proposed that online service providers be required to detect whether their subscribers are using a VPN to “publish, comment, or interact” with the platform. If a provider spots that a user is connected via a VPN server, it must block that user.

Not suprisingly, the proposal did not go down well with the French public, and has immediately being labeled “Orwellian.”

Faced with mounting backlash, Belhamiti withdrew the amendment just a couple of days after its introduction. In a lengthy-worded post on X, Belhamiti claimed that he did not expect the amendment to be approved in the first place (!). The lawmaker went on to claim that he merely wanted to spark a debate and draw attention to the issue of online crime and VPNs.

“By tabling an amendment aimed at prohibiting publication (and not consultation) on social networks via a #VPN connection, it is quite obvious that I do not imagine its adoption as it is.”

It’s up to you to take Belhamiti’s words at face value. As far as we are concerned, it seems more likely that pressure from privacy advocates and the public at large got to the lawmaker and forced him to backtrack. Also interesting is the way Belhamiti tried to draw a line between using a VPN for posting/sharing (“publishing”) and viewing (“consulting”) content. According to the lawmaker, only the former should be prohibited, which makes the idea even more confusing. If this becomes the case, providers will have to somehow distinguish between users who use VPNs to consume content and users who use VPNs to also create content. Sounds completely far fetched if you ask us.

Belhamiti’s withdrawal of his amendment is a victory for the defenders of privacy and online anonymity. But we should not exaggerate the significance of this local triumph: the battle may be over, but the war rages on.

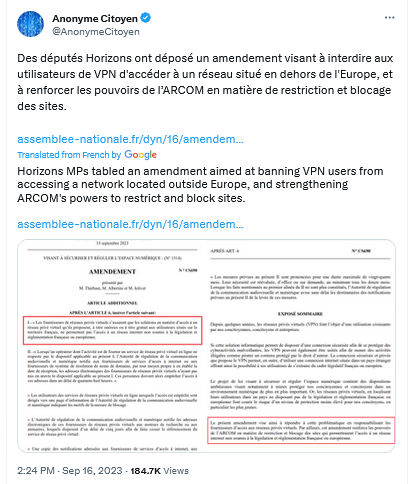

Somewhat overshadowed by Belhamiti’s now moot proposal has been an amendment to the same law put forward by a group of deputies led by Thiébaut. This amendment may not have gotten as much press, but it is just as damaging.

Great Firewall of France?

Thiébaut’s amendment does not ban VPNs outright, instead it strives to make them useless (for many popular use cases, at least). The amendment requires VPN providers to ensure that their services “do not allow access to an Internet network not subject to French or European legislation and regulations.” The wording leaves a lot of room for interpretation, but its intention seems clear — to relegate the French Internet to the French government’s backyard. This cannot but remind us of the “great firewall of China,” a regulatory and technological system of internet censorship that allows Beijing to filter and block online content for users within the country.

The amendment also empowers the French Audiovisual and Digital Communications Regulatory Authority (ARCOM) to notify ISPs and DNS resolvers of any VPNs that violate the rules. Within 48 hours of being notified, they must prevent users from connecting to the offending VPNs. An order to block a particular VPN for non-compliance can last up to 24 months.

Unlike Belhamiti’s amendment, Thiébaut’s is still up for debate in the French parliament. And even if it fails to pass (which we certainly hope it does), there’s no guarantee that a similar amendment won’t slip through the cracks, unnoticed by the public, and become law.

One thing that can be taken from this is that the part of French society that values its anonymity and privacy should brace itself for an uphill battle and remain alert in the face of government attempts to make VPNs illegal in the country, either directly or indirectly. Everything suggests that there will be multiple of those in the future.

For the time being, the use of a VPN is legal in France as well as in the majority of countries in the world. Countries that have banned or severely restricted the use of VPNs usually justify their actions as aimed at protecting the public good. The French deputies are not an exception from this trend: they spin their proposals as necessary to protect children or stop the dissemination of illegal content. However, the premise for the bans is flawed, and stems from a misrepresentation of what VPNs are and how they work.

The majority of people who use VPNs are legitimate users who are not doing anything illegal. They just value their online rights and freedoms and want to protect their privacy from the prying eyes of ISPs, who can track their every move online if it is not obfuscated. Those who use VPNs to commit crimes are an absolute minority, and banning VPNs to identify them seems a dubious and disproportionate solution. Criminals will find a way to hide their online identities regardless, while casual users would be left without an important tool to protect their privacy and shield their personal sensitive information from both the increasingly inqusitive government, and cyber criminals.