Copilot hits a legal curb: GitHub’s AI assistant is accused of software piracy. What does this hold for AI?

“What’s yours is mine, and what’s mine is mine” was apparently the principle that guided Microsoft, GitHub, and OpenAI as they were developing Copilot, an AI-powered coding assistant. At least, that is what the class-action lawsuit against the trio implies.

Released in June 2021, Copilot is billed by GitHub as an “AI pair programmer” able to “suggest code and entire functions in real-time”. When fed a natural language prompt, CoPilot answers with blocks of code. It is able to do so thanks to another AI product, Codex, that was developed by OpenAI and is integrated into Copilot. Copilot is available for GitHub programmers in exchange for a subscription fee of $10 per month or $100 per year.

OpenAI trained Copilot on code from publicly accessible GitHub repositories. While Microsoft says that Copilot was trained on “billions of lines of code”, it does not explicitly mention how it stumbled across such a treasure trove. According to the lawsuit, spearheaded by programmer and lawyer Matthew Butterick, that’s where the problem lies.

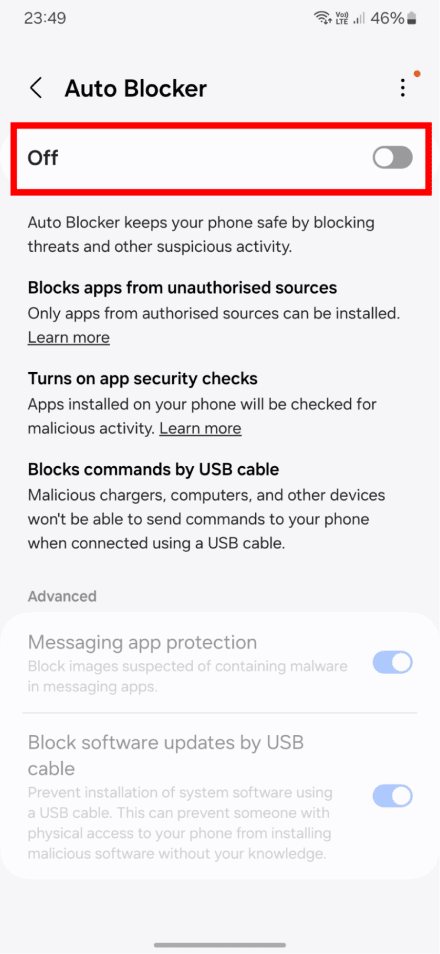

The complaint argues that the tool violates open source licenses of GitHub users that Microsoft pledged to respect after buying the platform in 2018. Namely, the lawsuit accuses Copiloit of failing to display copyright information or somehow indicate that its output is derivative, and argues that it is “thereby accomplishing software piracy on an unprecedented scale”. The lawsuit alleges that Copilot “often simply reproduces code that can be traced back to open-source repositories or open-source licensees.”

For its part, OpenAI argues that Codex should be exempted from license requirements because it meets the definition of “transformative fair use.” The company says that the open source code was used as training data “for research purposes” and has never been intended to be included “verbatim” into the output. It goes on to claim that over 99% of Codex’s output “does not match training data.”

But plaintiffs allege that it is exactly what’s happening.

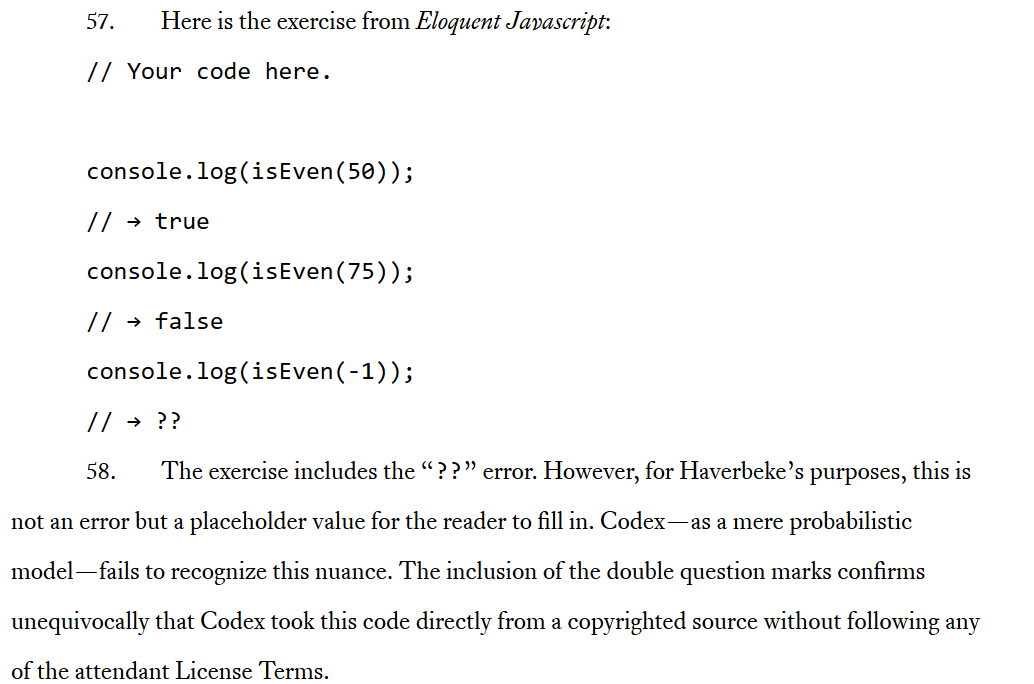

As an example, the complaint mentions Eloquent Javascript book by Marijn Haverbeke, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial license. The code in the book is also licensed under an MIT license. Under the terms of that license, Copilot is required to include a copyright notice and a permission notice, but it does not do so. That is because Copilot has not been trained to follow any license terms by design, the lawsuit says. It then explains in detail how Codex effectively copies code directly from copyrighted sources, including from Haverbeke’s book.

Screenshot: Excerpt from the lawsuit detailing how Codex allegedly copies code “directly from a copyrighted source.”

It’s not only Butterick who is pointing to the questionable premise on which Copilot is built. Last month, developer and professor of Computer Science at Texas A&M Tim Davis came to very much the same conclusion. Davis tweeted that Copilot parroted “large chunks” of his copyrighted code without attribution. Moreover, the AI-powered assistant even appeared to recognize that it was Davis’s code it was copying. The researcher said that when he prompted Copilot to produce code “in style of Tim Davis,” he got a “slightly tweaked” version of his code. The Copilot inventor, Alex Graveley, played down the similarities, arguing that the code was “similar, but different.”

While there has been an eternal debate about where one draws a line between plagiarism — that is presenting someone’s else’s work as your own without giving so much as a shout out to the original author — and inspiration, the lawsuit says that Copilot is more like the former. Despite the companies’ assurances, “in practice … the output is often a near-identical reproduction of code from the training data,” the lawsuit charges.

The plaintiffs also take aim at the OpenAI’s argument that using open source code to build a commercial product constitutes “fair use” and benefits the open-source community. Such use “is not fair, permitted, or justified,” the lawsuit says, accusing Copilot of seeking to “replace a huge swath of open source by taking it and keeping it inside a GitHub-controlled paywall.”

In a separate blog post, Butterick describes Copilot as “merely a convenient alternative interface to a large corpus of open-souce code.” And if it is so, then paid Copilot subscribers may unwittingly violate open source licenses of fellow developers. But according to Butterick, the issue runs deeper. By serving as an intermediary between open-source authors and beginner programmers, Microsoft removes “any incentive” for Copilot users to discover open-source communities. In the long run, it can deal a devastating blow to the open-source community as a whole, robbing it of engagement that would instead move to “the walled garden of Copilot,” Butterick argues. Calling Copilot a “parasite” that leeches off open-source contributors, he accuses Microsoft of a “betrayal of everything GitHub stood for.”

Consent not required

It can be tempting to blame the Copilot controversy entirely on one bad actor, Microsoft. The tech giant is closely intertwined with OpenAI, having invested $1 billion into the company and looking to invest more. It could be argued that Big Tech as a whole has a habit of milking off user data for profit (we don’t need to go further than Meta and Google), but it also does not help that there are no rules or standards around AI systems training.

Legally, there’s nothing stopping companies such as OpenAI and Stability AI (best known for its text-to-image generator Stable Diffusion) from training their AI models on personal information, copyrighted content, medical images… basically anything that has even been posted online. The datasets on which these generative AI models are trained are made up of large amounts of unfiltered data scraped up from all over the internet. It’s up to a company behind a certain AI product to refine it by weeding out any offensive or sexually explicit texts and images. However, AI firms have little incentive to go beyond that. Tools such as Have I Been Trained help users search their data among publicly available AI training materials so that they can request its removal, but it’s a drop in the ocean as far as privacy and data protection go. First, it’s not easy to find it there, and second, no one guarantees that it will be deleted. Moreover, if you have found your data in the dataset, it means it has probably already been used for AI training and may have already become part of some AI-powered product.

That is, in practice you can only opt out of your data being used for AI training only after the ship has already sailed. The Copilot case seems to have been the first time anyone has challenged the AI learning mechanism and its output in court, and is therefore a milestone, but the criticism has been mounting for quite some time. Earlier this year, a UK-based artists’ union launched a campaign to “Stop AI stealing the show.” One of its core demands is for the government to make it illegal for AI to reproduce artists’ performances without their consent.

Thus, the lack of an opt-out mechanism and the issue of consent have been brought to the forefront of the AI debate.

It is not what you do, it’s how you do it

As Butterick writes, the main objection of creators’, be they programmers (as in the Copilot case) or visual artists, is not to AI technology in general, but to the way the companies that create these tools condition them to act.

“We can easily imagine a version of Copilot that’s friendlier to open-source developers — for instance, where participation is voluntary, or where coders are paid to contribute to the training corpus,” he writes.

Some platforms like Getty Images are banning AI-generated art altogether, others trying to move in the direction outlined by Butterick. For instance, Shutterstock, which has recently begun selling AI-generated content as part of its partnership with OpenAI and LG, announced that it would be adding an opt-out function to contributors’ accounts. That function “will allow artists to exclude their content from any future datasets if they prefer not to have their content used for training computer vision technology.” In addition to that, Shutterstock set up a Contributor Fund, which would be used to compensate the artists whose IP was used in the development of the AI-generative models. DeviantArt is likewise providing creators a way to block AI systems from scraping up their content. A special HTML tag will apply to the pages of the DevianArt artists who requested that their work is exempted from AI training. Third parties will have to filter out content with the tag under the platform’s terms of service. It’s worth noting that, technically, AI systems will still be able to vacuum that data up.

However, such goodwill examples are far and few between, and it’s unlikely that they will become a norm without proper regulation. The Copilot lawsuit, aside from shedding more light on the issue of AI training, may as well trigger that necessary shift. And even if one complaint is unlikely to change the system, it may cause a domino effect, paving the way for similar legal challenges and eventual regulation. Seeing as new AI products are popping up like mushrooms, we need to rein in the companies behind them before it’s too late and they’ve already gobbled up all our data.

Compounding the problem is the fact that Big Tech companies, notorious for their disregard for privacy and protection of user data, are leading the AI revolution. It has been reported that Google is working on several AI code projects, including one codenamed Pitchfork. The secretive tool, that is now still in development, will reportedly see AI writing and fixing its own code. The idea behind the project was to streamline updates to Google’s Python programming language codebase. Namely: to get rid of software engineers, and let AI do the work. According to Business Insider, that spoke to sources at Google, the project’s objectives have since shifted to make the tool more of a “general-purpose system.”

New technology, old pattern of data misuse

It remains to be seen what will come out of the GitHub programmers’ attempt to challenge Copilot and whether it has a ripple effect on the industry as a whole. On the one hand, the AI problem has emerged because the technology that powers generative AI systems is new and meanders in the gray territory between fair use and copyright infringement.

On the other hand, the problem is as old as the hills. At its heart is the mishandling of user data by tech corporations that treat it as their own. We can try to solve the AI-specific part of the conundrum by conceiving some rules and regulations, but as we’ve seen from the EU and US attempts to protect our personal data from Big Tech, even the most stringent laws are not a panacea. Big Tech will always be looking for loopholes and workarounds to sidestep privacy rules and data protection laws. But that doesn’t mean that we as a community shouldn’t put pressure on governments to develop these rules, and on tech giants to comply with them.